From backfield to bobsled, Tomasevicz’s unlikely journey

Photo by AP Photo

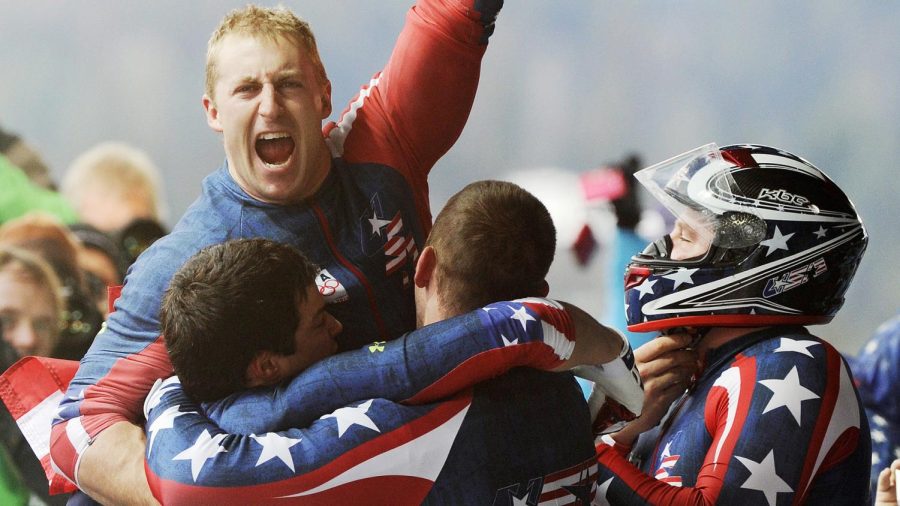

Curt Tomasevicz celebrates with his teammates after winning the four-man bobsleigh competition at the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics in Whistler, British Columbia on Feb. 27, 2010.

For Curt Tomasevicz, it was a long way from Memorial Stadium to the Swiss Alps.

And it came with many stops along the way for the former Husker running back and Olympic bobsledder – including Olympic Games in Turin, Vancouver and Sochi.

This winter, Tomasevicz found himself in Switzerland, but instead of pushing a bobsled, he was helping pick the U.S. bobsled team members that competed at this year’s Winter Olympics in Beijing.

Long before Tomasevicz slid down his first course, he was a UNL student-athlete, playing running back and linebacker for the Huskers from 2000 to 2003. He didn’t get much playing time over his career with the Huskers, but Tomasevicz credits some of what he learned on the gridiron with preparing him for his career on the icy slopes.

“Training for pushing a bobsled is similar to training for football in that you need to be fast and powerful for short amounts of time,” Tomasevicz said. “Overall, you need to train for both with sprinting and lifting.”

Tomasevicz picked up bobsledding in 2004 after being talked into trying out for the U.S. National Team by Amanda Moreley, a UNL women’s track athlete who had been recruited by the Women’s National Bobsled team. Tomasevicz flew to Calgary, Alberta, for the tryout.

“I went through a sprinting and lifting test and then they taught me how to push [the bobsled],” Tomasevicz said. “I was then able to make the national team that year and worked my way up the depth chart until I was on the USA 2 sled for the 2006 Olympics” in Turin.

Success wasn’t immediate for Tomasevicz, he said. “It can take several years to learn the optimal technique for pushing, loading, and riding in a sled.”

Tomasevicz and his four-man crew put on a solid performance in Turin finishing sixth.

Four years later, Tomasevicz returned to the Olympics — this time in Vancouver, where he and his four-man crew defeated Germany by 0.38 seconds to win the gold medal.

“It is hard to put into words what it was like to win the gold medal,” Tomasevicz said. “I remember standing on the podium and the moment went by so fast that I remember thinking that I didn’t have enough time to soak it all in.”

In addition to taking home a gold medal in Vancouver in 2010, Tomasevicz also enjoyed his Olympic Village experience.

“The Olympic Village is a unique experience because there are only athletes allowed there,” Tomasevicz said. “One of my favorite memories is playing Rock Band with some Italian speed skaters and a Greek ski jumper in the athlete lounge in the village.”

Four years later, Tomasevicz and his four-man crew followed up their gold medal with a silver medal in Sochi. His crew originally won bronze, but the Russian team was eventually stripped of the silver medal for doping.

Tomasevicz retired from bobsledding after the 2014 games and returned to school at UNL where he earned a Ph.D. in Biological Engineering in 2017. He currently works as an Assistant Professor of Practice in the department of Biological Systems Engineering at UNL where he is involved in teaching several classes. Even there his Olympic experience has an impact.

“I think part of his [Tomasevicz’s] special skill is that he is a really good listener,” Dr. David Jones, department head of Biological Systems Engineering at UNL said. “In a colloquial way he can read the audience and the students, and tune his communication to the room.”

Nowadays, it’s not so much about pushing a sled. But it’s still about pushing.

“I learned a lot about pushing myself to my limits physically and mentally, [through bobsledding]” Tomasevicz said. “I also learned a lot about patience with myself when learning something new.”

He may not wear the sledder’s helmet or the skin-tight, Lycra uniform, but he carries some important Olympic lessons with him into the classroom.

Hi! My name is Jacob Bundy. I am a senior here at Lincoln East and this is my first year on the Oracle staff. I love to watch sports, go on walks, listen...