Letter grades, should they pass or fail?

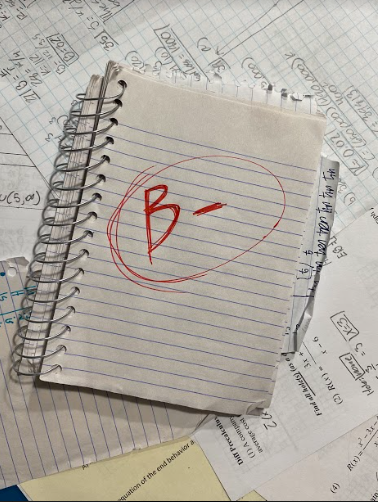

Photo by Kylie Brown

A look into how work accumulates into a grade, taken October 26, 2022.

What’s the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of the public school system? Is it cartoon caricatures of a schoolhouse? Classrooms full of learning students? Or is it grades?

One thing that always comes to mind when thinking about schools is the decades-old letter grades. Excelling A’s, succeeding B’s, and passing C’s; these grades are responsible for easily conveying classroom information and are deeply ingrained into our modern day education as the very concept of successful educational assessment. But, while it seems simple and convenient enough, how often have we actually stopped to consider the consequence of simplifying a student’s grade down to a single letter? Because if we shine even a glimpse of light on the subject, we can see that grades have evolved into a major problem, and one that’s diminishing the integrity of the American public school system as a whole.

When public schools were first established in the early 1800’s, the primary objective was to prepare young people to become competent democratic citizens. As time went on however, the focus of schools shifted away from basic life and political skills, and more towards advancing individual education. And while the pursuit of knowledge and the drive to learn is a great goal, there’s one major hiccup in the system that evolved over the last several decades and is crippling the whole process: oversimplified letter grades.

The modern day A-F grade system as we know it wasn’t widely implemented until the 1940’s, and up until then, even though schools still used marking systems, most schools actually avoided sharing students’ marks with them, out of concern that competitive environments would distract students from actually learning and would have negative consequences towards intellectual development; a theory primarily funded and advocated for by early 1800’s father of the public school system, Horace Mann.

“If superior rank at recitation be the object, then, as soon as that superiority is obtained, the spring of desire and of effort for that occasion relaxes,” Mann wrote in his ninth annual educational report.

Mann understood the risks a competitive environment would pose to student learning, and throughout his founding of the educational system, advocated against it, instead supporting the creation of curriculums that excluded dividing and classifying systems.

But what do we see nowadays? Almost the exact opposite of what educators warned against; an environment where grades are passed back mere days after turning in work, and oversimplified class grades are on constant display, able to be analyzed and fretted over. Students of today are left focused on the grades they receive rather than the education, and this leaves them at risk for shortcut solutions, lack of motivation, and harmful beliefs about themselves and others.

At first, the concept of letter grading may seem extremely beneficial, both to the students, their families, and the school system as a whole. Letter grades simply convey the success of a student, reflect their abilities, and encourage those with lower grades to improve. Letter grades can also motivate high-achieving students, allow parents to easily understand how their kid is doing in class, and give teachers a simple enough system to grade their pupils by. In theory, letter grades seem an efficient and effective way of measuring student progress in a manner that is quick and productive.

However, what these arguments fail to consider is the immense consequences that such simple grading causes to those graded by them. While it’s true that the current grading system is founded on the idea of streamlining communication between parents, schools, and other parties, what it isn’t founded on is improving student learning or wellbeing, and as such the school system is swamped with unintended, now normalized consequences.

Assigning students grades at such young ages bottlenecks their motivation to learn by teaching kids to value themselves by a letter or number, and because of this, much too early on in life classes become all about ‘winning’ and not learning. Most students’ grades are their biggest motivation to succeed at all in school, and rather than cultivating a genuine interest and passion to learn, this nearsighted system of priorities negatively limits the way students view education and learning at developmentally inappropriate ages.

Higher letter grades are intended to be used to identify high-performing students, but because of this openly known ranking system, grades can negatively impact students’ self worth at early ages. Not only that, but because of the practice of averaging – where all of a student’s grades accumulated over the time of the class are put into their final grade -, even if students do honestly succeed in the material, their previous struggles will negatively impact their final grade and inaccurately display their total understanding, which can cause them to devalue their own intelligence solely because of the consequence of not immediately understanding all new material.

So much of student mental health is tangled up in the toxic culture that occurs by indirectly training kids to associate their self worth with a number, implying that their worth as a person is good or bad depending on their grade. In the long run, this self-deprecating, stressful environment can cause burnout, self hatred, worthlessness, and causes students to feel dumb and disincentivized to try again if they fail.

And these problems aren’t even including the complications letter grading causes for teachers. Teachers spend an average of 300 hours grading per year, but almost none of that time is spent on actual useful feedback. Instead teachers spend most of that time converting scores into letters, and are rarely ever able to give the needed advice to students, when in reality that’s what is needed: communication between students and teachers.

Letter grades don’t give students feedback, and neither do percentages. By establishing a more convenient and simpler way of displaying grades, students are losing some of the most crucial assistants in actually improving their grades; feedback. In order to receive feedback, students have to take time out of their schedules to find their teachers outside of class, something they don’t have the time to do on a regular basis, and something teachers may not have the time to do either.

So with all the obvious consequences of the letter grading system, what are we still using it for? Is convenience really so important as to sacrifice the mental and physical health of the students and educators living by its standards? Is there something we’re missing? Something that letter grades bring that somehow makes up for the terrible way they structure the merit and scoring of students across America? The truth seems to be no.

“Ditching traditional letter grades reduces stress levels and competition among students, levels the playing field for less advantaged students, and encourages them to explore knowledge and take ownership of their own learning,” A study done by Education Week in 2019 reported.

Students get no direction for improvement from a letter or number attached to their work: only when their grades are accompanied by personalized feedback and recommendations for how to improve. Feedback loops are critical for both those who succeed and those who struggle, and without them, it’s been well proven that the chance for student growth diminishes.

The fact remains that there are several methods of actions schools could and should take in order to better their grading system and direct it away from a class-based numerical, letter-based grade. For example, districts could stop letting kids with low grades automatically pass. It’s an issue not as commonly realized, but several schools are guilty of valuing quota rather than providing actual education for their students.

“I think some things are more about money and getting funded rather than what’s best for the kids,” an anonymous teacher at Lincoln East said. “A big complaint among teachers – not just in the district, but nationwide – has been them passing kids who don’t deserve to pass, because the district gets in trouble when they don’t have enough kids passing. I think sometimes we set kids up for failure.”

And these are by far not the only possible methods of reform; there’s several changes educators and schools can make to improve the grading system; such as eliminating the practice of affecting grade based off of things like attendance, participation, attitude, and extra credit that distort the accuracy of grades and turn it into a system of nonacademic achievements rather than a reflection of learning, or giving students should be given multiple chances to try again, to grow and master what they’re taught, rather than being forced to move on even if they still don’t understand a concept.

There are countless ways schools can improve by eliminating letter grades, and countless paths these school systems can go down on the road to improvement. But what matters most right now isn’t the exact way schools choose to change however, it’s that schools need to acknowledge how harmful the letter grading system is, and begin to reform grading away from classification-based systems like it. The possibility for change has been and will always be there, but right now we just need to wait for schools sto take the first step towards reform, and hopefully towards the better education of their students.

Kylie Brown is a senior at East, and this is her third year on the Oracle staff. Her favorite thing about the Oracle is that everyone knows each other,...