Investigation: Should schools be in full remote learning right now? (Part 3)

Part 3: Administrators explain the hard decisions they’ve had to make this year due to Covid-19 at the school level, district level

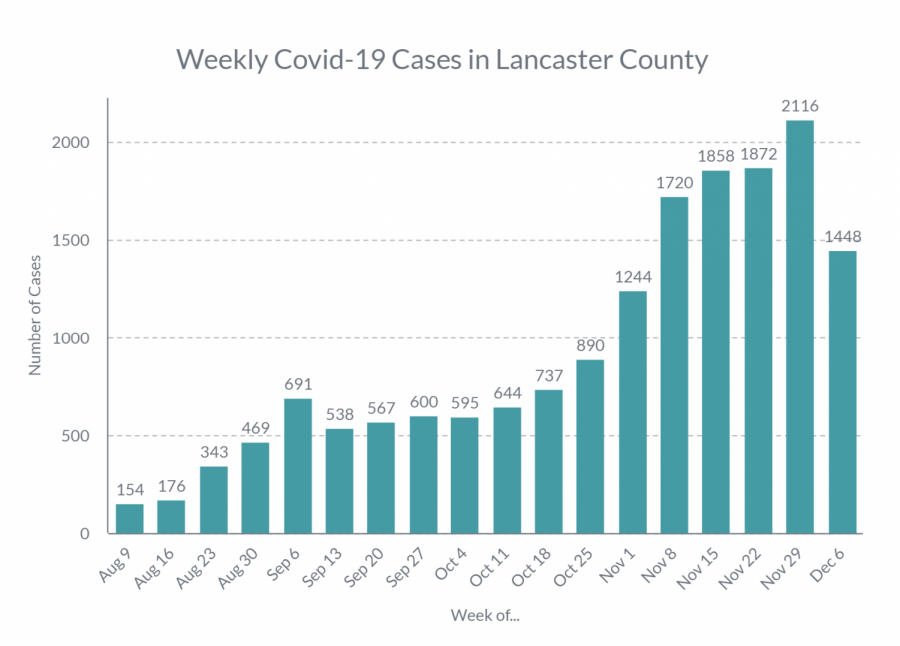

Photo by Lancaster County Health Department

This graph shows the number of Covid-19 cases Lancaster County has had each week since school started up. Numbers like these have aided controversy about whether or not students should be in full remote learning right now.

In this series, we’ve already looked at East student and staff perspectives (check out the student and staff articles here), but they aren’t the ones making all of the decisions. That falls some to the school level, with principals and administrators at East, and some to the staff at the LPS District Office. In this part of my investigation, we’ll cover both of those perspectives.

East Principal Sue Cassata explained a lot about how some of the different decisions are divided up and delegated to different personnel. In a pandemic with such a wide range of different problems to think about and everyone in the community affected, she doesn’t make all of the decisions regarding East High. Instead, she is given general guidelines to follow, and allowed to make more specific decisions that can only be made by someone in the environment the decisions concern.

“So during the course of the summer when the district was developing their plan, different buildings and principals and individuals were on different committees and they gave input into the plan,” Cassata said. “… then that would then be vetted against what the Lancaster County Health Department said… Then the district has said, you need to think about, and then given us these broad parameters of thinking, so entrance into the building, dismissal time, how to line up – those things were all recommendations given to every building and then each building then came up with its own plans. Many of the things that are on the document, our district also negotiated with the Lancaster County Health Department, which isn’t a part of the conversation that I have.”

Some of these decisions are also made with communication between the administration at each of the high schools. “I’m in a principal group, and we meet every week then to discuss the other pieces,” Cassata said. “So what we’ve discovered through the pandemic is that there are some things that are just important that all buildings do the same way at the same time. Whereas before, I think pre-pandemic, it was important that we had the same policy, but how we implemented the policy could be different.”

All of this collaboration up and down the ladder and between schools can really complicate things, especially when decisions and solutions are needed immediately. “[When there’s a problem] we bring it to the attention of somebody else, but it takes a week or so for that decision to be made, and at that point, the issue is no longer relevant,” she said. “That’s been kind of a frustration for many, with the immediate need to solve some things, [the problem] has to go through four or five layers now, where previously if it was a problem, we’d fix it and move on.”

Cassata is also involved in the contact tracing process at East as a sort of go-between through the various levels. She works with the health office to figure out a Covid-19 positive student’s schedule, then works with the staff they were in contact with to find any high-risk close contacts.

“So we ask all these questions, then I collect all the answers to those questions and give them to the district, who then communicates the responses to the health department, and then in collaboration with the health department, we make a determination of any close contacts,” Cassata explained. “And then we began notifying students and families if we have questions or concerns about those pieces. But when we get a report that is positive, we have to wait for confirmation from the health department before we can do any contact tracing. And if the health department then does their own contact tracing in addition, they’ve already started asking some questions, so they may tell us we’ll need to look at this [something more specific].”

With all of the complications and red tape of making decisions during a pandemic, Cassata asks students and parents to keep a couple of things in mind. “None of the decisions are made lightly,” she said. “The intention is not to take away a student’s experience at East High School. We don’t intend to suck the joy out of every existence. But our goal is to make sure we’re able to stay open. Our goal is to make sure kids and staff are safe, which in the pandemic requires a certain amount of diligence.”

“With all of this, I wish it wasn’t political,” Cassata continued. “I wish people didn’t associate if I’m wearing a mask, I’m this, or I’m not wearing a mask, I’m that. I choose to enforce face coverings because that’s what’s going to be safest for kids and if that’s what’s safest for kids then I’m going to do it. And I need people to understand that none of this is easy, and that we’re all doing our best. And that name calling because you disagree with what I have to enforce isn’t helpful.”

A lot of people forget that Cassata isn’t just a principal though – she’s a human being with a life outside of her job just like everyone else. As part of that life, she also brings to the table her perspective as a parent. “Becoming a parent has impacted all of what I do as principal, not just Covid-19 or non Covid-19, because I appreciate what parents want more for their children,” Cassata said. “I think before I knew it, I understood it. I understood what your mom and your dad want for you when you go to school. And I wanted to make it happen. But I didn’t have an emotional attachment to that.”

“So now as a parent I have an emotional attachment to see that that happens. When somebody calls and is upset because something hasn’t happened for their child, my heart actually hurts because that’s never what was intended. And so I think in terms of Covid-19, what I want for all parents is I want them to feel as comfortable sending their child to East as I feel comfortable sending my child to Humann.”

At the LPSDO level, Dr. Pat Hunter-Pirtle, the Director of Secondary Education has another, different level of insight into some of the decision-making processes in schools. “Ultimately, it is the superintendent of schools, Dr. Steve Joel, who makes that decision with his executive team,” Hunter-Pirtle said. “So that includes Matt Larson, Liz Standish, Eric Weber, John Neil, those people… But a lot of what they rely on is information from the Lincoln/Lancaster County Health Department, the mayor’s office, Pat Lopez, who’s head of the Health Department. Then one of our board members is Dr. Bob Rauner, who is a doctor. This kind of area is really his expertise.”

“So when a decision is being made, there are lots of people who are being consulted,” he continued. “This is not something that the district does, just on its own. And they’re meeting with the health department, probably at least two, maybe three times a week. So they’re doing this with lots of information, and when a decision is made, there’s lots of experts who are giving their best advice.”

Hunter-Pirtle also explained more about why being the red zone on the Covid-19 risk dial does not equate to having all of LPS schools and programs shut down. According to the data available now, students seem to be safer in schools.

“If you look at the cases, there are very few cases that spread at all in elementary, and even less so in middle school,” Hunter-Pirtle said. “And so, if you look at some of the information that’s provided by the Lancaster County/Lincoln Health Department, the rate of spread in schools is significantly lower than it is in the community. And so, really, when you think about that, the best place for kids is in school.”

“Now, the hard part is we can’t control, mainly talking about high school kids, we can’t control what they do when they leave school,” Hunter-Pirtle continued. “So for instance, you can do everything at school, like how much you’re wearing face coverings, how much you’re sanitizing, how much you’re washing your hands, sanitizing hands, sanitizing desks after you leave a class and all of that, so you’re doing all of that. But then those same kids may be piling in a car at lunchtime with five or six other kids and going out to lunch, and most likely not having masks on, and that kind of thing. So that’s the hard part that we don’t control [that allows the virus to spread].”

Another factor in some of the decisions that have been made is how well students learn on Zoom. Grades have been significantly worse this year in correlation with Zoom learning, and as long as there’s not a lot of evidence of spread in schools, it’s better to keep people in person.

“So this is my 42nd year in education and when we started [zoom] last year, in mid-March right after spring break, that is the hardest work I have ever done,” Hunter-Pirtle said. “Because basically from that time until August, all I did was virtual zoom meetings all day long, and write planning documents. At the end of the day, I would be exhausted, much more so than compared to when it’s a normal school year. Most of my days [during a normal year] are spent out and about in school… But the thing about being in person and seeing people in person, rather than behind a computer screen, just makes a huge difference. And so again, we just really believe the best place for kids is in school.”

Regardless of the difficulties zoom learning has caused and will cause if LPS decides to go to full remote, there have been some upsides from these adaptations. “There probably will be some things that we may never go back and do it the way it used to be because of being able to zoom,” Hunter-Pirtle said. “…An example I’ll give you is parent teacher conferences. Administrators and teachers really liked being able to talk to a family, not in a gym, not standing in a line. They could really have pretty honest conversations and parents tell us they were more willing to talk about their students then when there’s somebody right behind them in line in a gym, who could be listening in on the conversation.”

Keeping all of this in mind, according to Hunter-Pirtle, LPS’s goal is to go remote only on a small scale, and avoid even that if at all possible. There have actually already been examples of this within different schools already. “We had an elementary school where there were three fifth grade teachers and all three of them ended up in quarantine,” he explained. “One of them had Covid-19, but then the other two were close contacts. So those fifth graders went remote for a week or two, because there was just no way to cover that [with substitutes]. But so that’s the other hard thing is we want to keep schools open. But when this spread from the community starts to affect adults, then, we’ve got to think about if we can keep the schools open. Can we keep qualified adults in front of the classroom?”

This is certainly a very valid concern, and one we will dive into more in the next part of this series. Stay tuned for the upcoming article about outside perspectives, from both a government position and a health professional’s position.

My name is Julia Ehlers, and I’m a senior here at Lincoln East. This is my second year on the Oracle Staff, and I’m looking forward to another great...